Exploring Treatment Options for Scoliosis

When it comes to treating scoliosis, early diagnosis is crucial, especially in cases involving children and adolescents (1, 2). However, this also holds true for adults. During periods of rapid growth, such as during childhood and adolescence, scoliosis poses greater risks as it is more likely to progress and cause significant deformities and structural changes.

If the curvature of the spine becomes severe enough (beyond approximately 45 degrees), surgical intervention, including spinal fusion, is often recommended (3). In the case of adults, the size of the curve becomes less concerning since even small curves can cause pain and dysfunction (2, 4). Additionally, adults do not face the same risks of progression associated with rapid growth during the adolescent years (2, 5).

Understanding Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS)

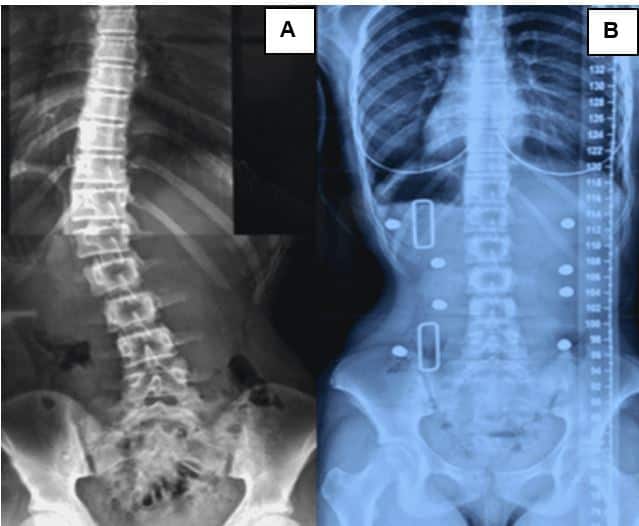

AIS is typically diagnosed in individuals aged 10 to 18 years when no other identifiable cause for the scoliosis is found (2). On the other hand, adults living with scoliosis may have AIS from childhood or may experience adult-onset scoliosis, known as adult de novo or degenerative scoliosis (6). Adult-onset scoliosis is often associated with spinal instability and the presence of listhesis (6). Scoliosis, by definition, involves a three-dimensional deformity of the spine characterized by a lateral translation of 10 degrees or more (Cobb angle) on X-ray, combined with rotation (2).

Treatment Options for AIS

Adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis, especially those at risk of curve progression during rapid growth periods and those with moderate to severe curves, benefit from early diagnosis (5, 7). Early diagnosis allows for conservative treatment options that can potentially eliminate the need for surgery (8). Physiotherapeutic scoliosis specific exercises (PSSE) are effective treatment options for curves up to approximately 20-25 degrees and have been shown to prevent the need for further interventions if initiated early (9, 10, 11, 12). An example of a PSSE program is ScoliBalance®, which combines chiropractic, physiotherapeutic, and exercise rehabilitation principles, utilizing the best available evidence-based practices (2).

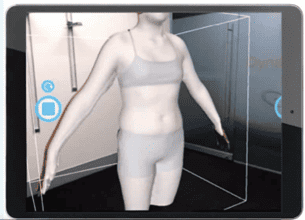

When curves progress beyond 20-25 degrees and growth continues in the child, PSSE should be combined with a custom-made, 3D brace designed using the BraceScan app to minimize human error in design and fabrication (2, 13). This brace is known as ScoliBrace® (14).

In cases where the curve exceeds approximately 45 degrees, a surgical opinion is often recommended, involving the fusion of the spine that was once mobile and flexible (Figure 4) (15).

Treatment Options for Adults with Scoliosis

Young adults with AIS may receive similar treatment approaches to adolescents, depending on the flexibility and deformity of the spine. In contrast, adults with de novo or degenerative scoliosis may also benefit from PSSE but are not selected based solely on curve size, as seen in adolescents. Additionally, a 3D custom-made brace can be helpful in managing symptoms such as pain.

Supporting Patients with Scoliosis

Adolescents facing a scoliosis diagnosis often experience unique stressors during a critical period of transition from childhood to adulthood (16, 17, 18). This diagnosis can disrupt the delicate process of gaining independence, resulting in potential stressors such as decision-making, uncertainties, numerous appointments, multiple examinations, commitment to rehabilitation programs, and wearing a brace (16).

To ensure effective support, it is essential to consider the following strategies:

Ensure treatment is provided by a certified health professional who specializes in scoliosis-specific rehabilitation.

- Foster open communication within the healthcare team, involving the adolescent in meetings and planning.

- Empower the child by providing audio recordings of exercises, enabling them to practice under voice instruction and reducing potential debates at home.

- Adults with scoliosis also require support during treatment. However, clinical experience suggests that these patients are often more motivated as they seek assessment voluntarily, driven by symptoms like pain or a desire to avoid surgery. Since adults may not need frequent visits, it is crucial to equip them with self-management strategies.

Tips for Supporting Patients with Scoliosis:

- Encourage regular practice of the prescribed PSSE program.

- Be available to answer questions and refer any inquiries beyond your expertise to appropriately trained professionals.

- Consider expanding your knowledge in the field of scoliosis through specialized learning opportunities to ensure accurate identification of cases. Visit our website at https://scolicare.com/academy for information on short courses and upcoming webinars.

- Ensure patients have access to their treatment program and fully understand their responsibilities.

- Aid in their adjustment to wearing the brace by encouraging open discussions with friends and promoting acceptance rather than concealment. Monitor any pain or discomfort related to brace usage and promptly inform their clinician about any issues.

References

- Bunnell WP. An objective criterion for scoliosis screening. JBJS. 1984;66(9):1381-7.

- Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, Czaprowski D, Schreiber S, de Mauroy JC, et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis and spinal disorders. 2018;13(1):1-48.

- Anthony A, Zeller R, Evans C, Dermott JA. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis detection and referral trends: impact treatment options. Spine Deformity. 2021;9:75-84.

- Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, et al. Screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2018;319(2):165-72.

- Charles YP, Daures J-P, de Rosa V, Diméglio A. Progression risk of idiopathic juvenile scoliosis during pubertal growth. Spine. 2006;31(17):1933-42.

- Diebo BG, Shah NV, Boachie-Adjei O, Zhu F, Rothenfluh DA, Paulino CB, et al. Adult spinal deformity. The Lancet. 2019;394(10193):160-72.

- Lee C, Fong DY, Cheung KM, Cheng JC, Ng BK, Lam T, et al. A new risk classification rule for curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. The Spine Journal. 2012;12(11):989-95.

- Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Wright JG, Dobbs MB. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(16):1512-21.

- Schreiber S, Parent EC, Moez EK, Hedden DM, Hill D, Moreau MJ, et al. The effect of Schroth exercises added to the standard of care on the quality of life and muscle endurance in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis—an assessor and statistician blinded randomized controlled trial:“SOSORT 2015 Award Winner”. Scoliosis. 2015;10(1):1-12.

- Kuru T, Yeldan İ, Dereli EE, Özdinçler AR, Dikici F, Çolak İ. The efficacy of three-dimensional Schroth exercises in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Clinical rehabilitation. 2016;30(2):181-90.

- Kwan KYH, Cheng AC, Koh HY, Chiu AY, Cheung KMC. Effectiveness of Schroth exercises during bracing in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: results from a preliminary study—SOSORT Award 2017 Winner. Scoliosis and spinal disorders. 2017;12:1-7.

- Kocaman H, Bek N, Kaya MH, Büyükturan B, Yetiş M, Büyükturan Ö. The effectiveness of two different exercise approaches in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A single-blind, randomized-controlled trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249492.

- Kaelin AJ. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: indications for bracing and conservative treatments. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2020;8(2).

- Sanz-Pena I, Arachchi S, Curtis-Woodcock N, Silva P, McGregor AH, Newell N. Obtaining patient torso geometry for the design of scoliosis braces. A study of the accuracy and repeatability of handheld 3D scanners. Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 2022;46(4):e374-e82.

- Choudhry MN, Ahmad Z, Verma R. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. The open orthopaedics journal. 2016;10:143.

- Sanders AE, Andras LM, Iantorno SE, Hamilton A, Choi PD, Skaggs DL. Clinically significant psychological and emotional distress in 32% of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Spine deformity. 2018;6(4):435-40.

- Belli G, Toselli S, Latessa PM, Mauro M. Evaluation of self-perceived body image in adolescents with mild idiopathic scoliosis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2022;12(3):319-33.

- Mitsiaki I, Thirios A, Panagouli E, Bacopoulou F, Pasparakis D, Psaltopoulou T, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and mental health disorders: A narrative review of the literature. Children. 2022;9(5):597.